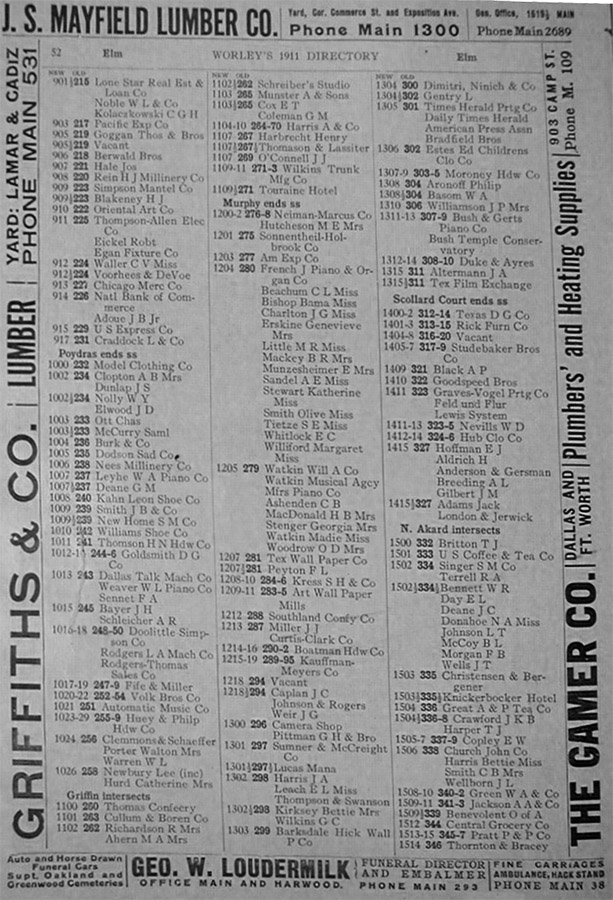

Before we begin, there's something important that needs to be noted: the addresses printed on cabinet cards produced in Dallas prior to 1911 are inaccurate to streets as they exist today. During the nineteenth century, multiple street names and building numbers across the city were duplicated. To deal with this problem, the city of Dallas undertook two major initiatives, renumbering streets for the first time in 1891 and following this effort with a second, comprehensive one in 1911. So while the business addresses found on vintage cards do accurately represent their corresponding studio locations at the time of production, they need to be converted to their modern equivalents before we can pinpoint those same locations today. The best resource for this - for images produced between 1891 and 1911 - is the 1911 edition of Worley's Street Directory of the City of Dallas, which provides a list of building numbers for each city street in two columns, with each "new" number being followed by the "old." This reference is sufficient for use with most of the Dallas cabinet cards in my possession. For cards produced prior to 1891, I've had to tie each studio to other businesses operating out of the same building as found in historical newspaper articles and period advertisements, then cross-reference those businesses with later articles and advertisements to determine the post-1891 addresses. Those addresses were then converted to their modern equivalents using the Worley's directory. The two successive waves of renumbering undertaken by the city are something to be aware of if you're working with early documents, or need to cite other reference materials dating to the early days of Dallas.

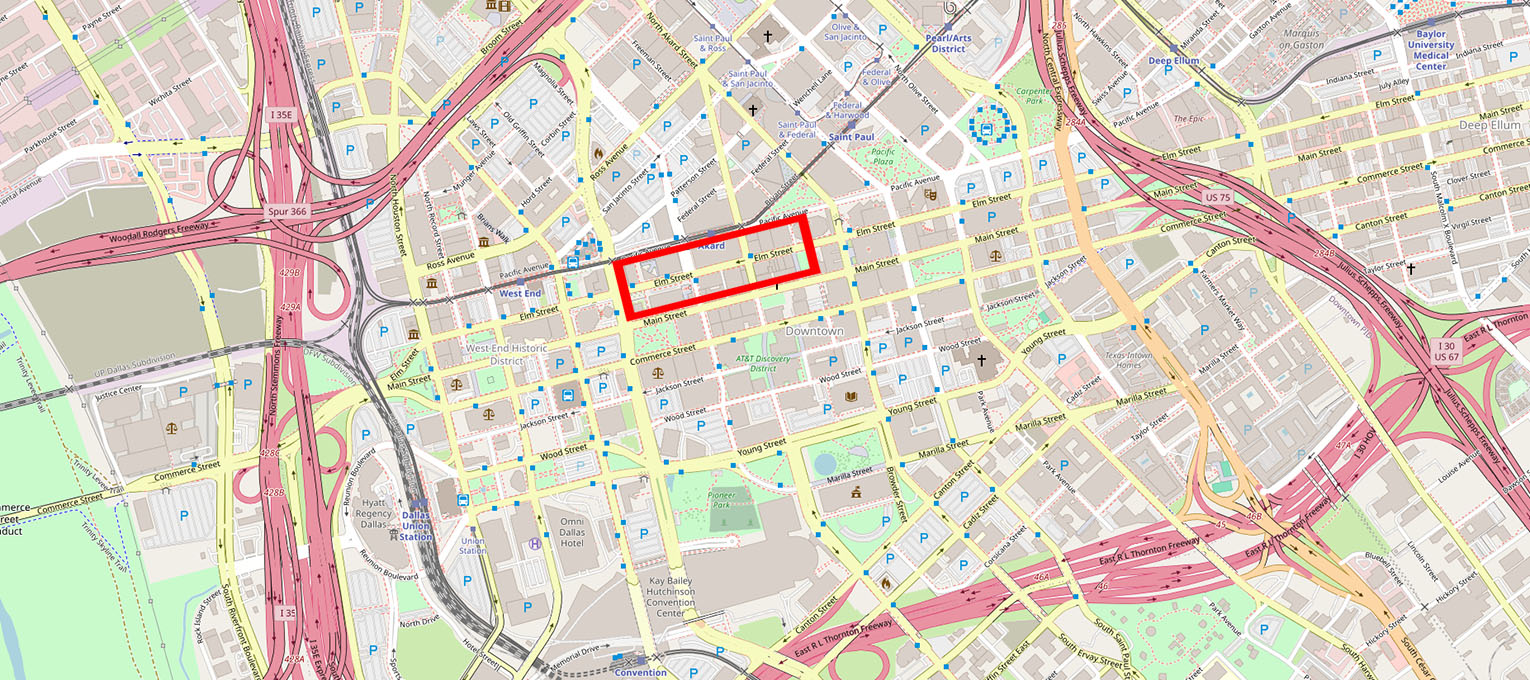

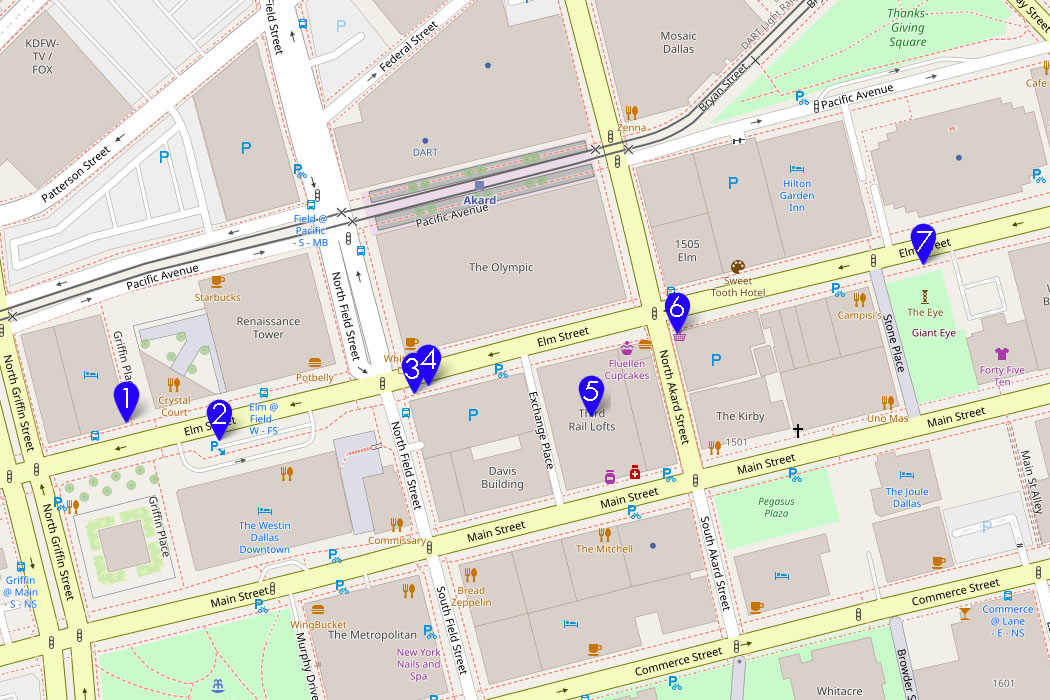

With that explanation out of the way, it's time to dive into the walk! As stated earlier, there are a total of seven locations we'll be visiting, all of them on Elm Street, and all within a roughly four block long stretch of about a quarter of a mile. Dallas was a much smaller community in the era of these studios, and its commercial core far more heavily concentrated inside the central business district. 1890s downtown was characterized by a mix of residential and business spaces which were often co-located inside the same buildings, with private rooms and residences often situated above commercial enterprises at street level. Some of these such rooms became the suites where enterprising photographers set up their portrait studios. Vanity cabinet cards of the type featured for this tour were popular from the later 1800s up until the advent of the first World War, but for this walk we'll be focusing on the period from about 1882 until the late 1890s. This represents the earliest period of mainstream cabinet card photography in Dallas.

1 - Hillyer

During the recession of the following year, the Austin studio was sold, and H.B. Hillyer & Son relocated to Dallas at the corner of Elm and Griffin. A Dallas Morning News article from July 1887 recounts the acquisition of an occupation tax license, and by 1888 the new studio was in operation at 701 Elm Street, with the studio's only appearance in the Dallas city directory taking place that year for "Hillyer, H.B. & Son." Cabinet card images produced during this time bore the imprint of "Hillyer & Son" in Dallas, Texas, but extant examples of these are now rare. More common are examples such as mine which point to locations in Dallas and in Belton, Texas, or, far more commonly, to Belton alone or elsewhere outside of Dallas. Hillyer's stay in Dallas was comparatively brief. By 1889, his space had been taken over by H. Jaenucke, with J.H. Webster associated with the space by 1891, and eventually by W. Wirt Williams. C. Ernest appears to have moved to Belton sometime between 1888 and 1889, with H.B. following him, and the two of them continued to operate associated photography studios for many years.

H.B. Hillyer is known to have been a member of the Texas State Photographers' Association, serving as secretary pro tem on at least one occasion. In addition to his photography work, he was also noted during his later years for his expertise in farming.

I mentioned before that we would come back to Griffin Street. Present-day Griffin Street is actually about two hundred feet to the west of the Griffin Street that intersected Elm during Hillyer's time. In fact, Griffin Place, which stretches today between the Homewood Suites and the Renaissance Tower's "Shop & Dine" building, marks the approximate location of the old street. So if you ever wondered why that crosswalk has a name, or why the block numbers don't change at the actual street intersection, you now know the reason why.

2 - Webster (1885-1889) & Church (1889-1900)

John H. Webster first set foot in Dallas in 1873, intending to relocate from the town of Marshall some 140 miles to the east. Unimpressed by what he would later describe as "an aggregation of saloons, gambling halls, variety shows and the like," he would return to Marshall, not coming back to the town he would make his permanent home until 1882. Suitably encouraged by what he saw as the town's forward development, he worked out of Hillyer's old studio before setting up shop at 804 Elm Street in an upstairs apartment of about 50 x 100 feet. As is the case with One Main Place, which stands today on the same site, entrance to Webster's studio was possible on two sides via either Elm or Main. The Tennessee-born Webster went on to make a name for himself during his tenure as commercial photographer not only through his work, but through his humorous newspaper advertisements. In these ads he regularly pitched his photographs as "worthless," "high priced," or "sure to displease," and frequently styled himself as "J.H. Webster, High Priced Photographer" or "J.H. Webster, H.P.P." On other occasions, however, he emphasized his expertise in photographing children, pointing out his acquisition of a "large lot of scenery specially adapted to children" and a selection of related designs bearing names such as "I love my dollie" and "I am my papa's pet."

Alongside his photography business, Webster was also active in real estate speculation, being a part of the first boom in 1885 and evidently transacting real estate deals inside the photography studio. An April 1888 Dallas Morning News advertisement has Webster "offering "to every housewife, clerk, wage-worker, etc., who are not able to pay cash, an opportunity to buy a home." Prospective clients interested in either photographs or real estate were thus encouraged to call upon J.H. Webster, H.P.P., at 804 Elm Street in Downtown Dallas. In 1889, following an unsuccessful run for mayor, Webster partnered with Charles O. Wood and moved to pursue real estate full time, with the newly christened Webster-Wood Real Estate and Guarantee Company opening for business one street south at 829 Main. The photography studio was thus sold to Clifton Church, whom Webster "cheerfully" recommended "as a gentleman with first-class business qualifications," and Webster went on to ride the real estate bubble through the panic of 1893 and onward.

Church would go on to make his mark in the industry at large, winning awards for displays of his work at the State Fair photographers' exhibit in 1891 and 1893. He served as Second Vice President of the State Photographers' Association, and Dallas, Texas, Through a Camera, a printed collection of engravings made from his original photos, was published in 1894. In early 1900 Church relocated his studio up the street to 336 Elm, and any record of him as photographer seems to end after 1907. Exactly what had prompted his move into the field of photography is lost to history, but it is known that he eventually moved back to his native Massachusetts, where he would die in 1943 at the age of 88.

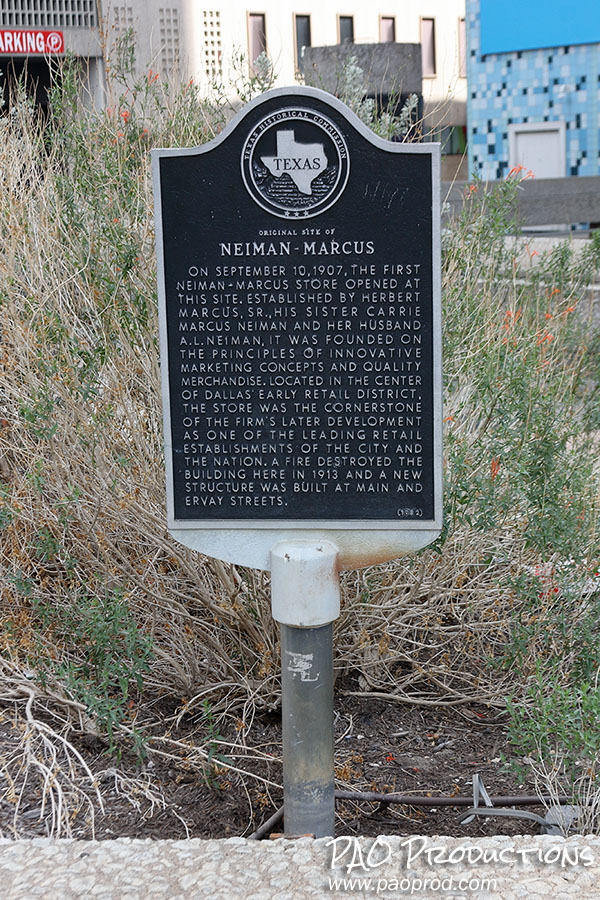

Today the One Main Place hotel and office building stands where the old Fourth National Bank, and its upstairs units which included those of Webster and Church, once stood. The entrance to the Westin Hotel marks the approximate location of the studio as of 2024, about two hundred feet to the west of the historical marker for the original Neiman-Marcus. On any given day in the spring, summer, or fall, you can see pigeons roaming freely around the area.

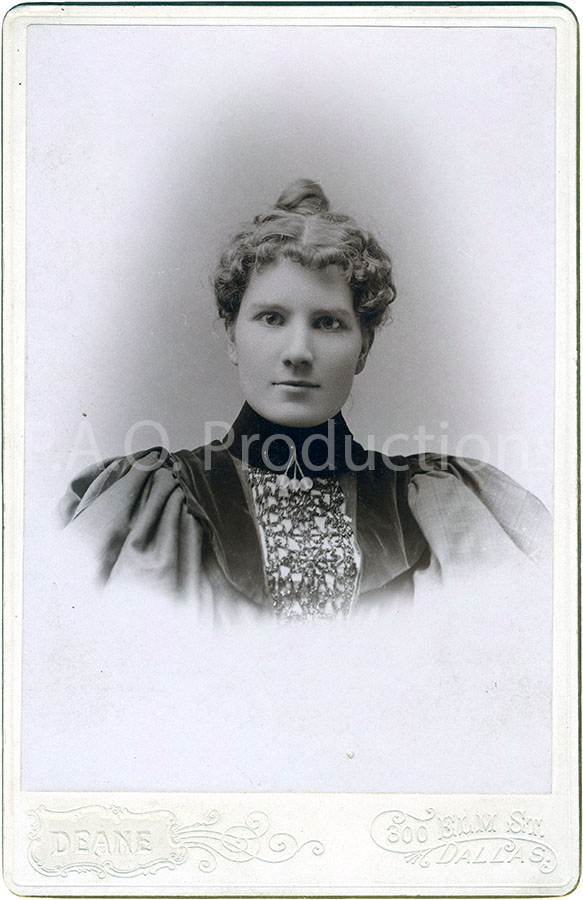

3 - Deane

Granville appears to have arrived in Dallas sometime in 1892. A notice in the Dallas Morning News from June of that year announced the opening of his studio, a "strictly first-class photographic establishment," in the space over Robinson's penny store at 300 Elm. The notice introduced him as a "thoroughly artistic photographer, late of Memphis, Tenn. and Galveston, Tex." who specialized in photographing children. Indeed, his numerous advertisements tended to highlight his "instant" photographs of babies "in novel positions" as often as they proclaimed his photos to be "the finest made." In the sheer number of advertisements placed in the News, he seems to have been surpassed only by Apex in the quantity and vigor of his claims. Some of the more notable campaigns published in the classifieds included an offer to give a photograph to "any man, woman or child over seventy years old" and one proclaiming that "Diptheria is dangerous... Have it photographed immediately by Deane, the baby photographer." And unlike competitor W. Wirt Williams a few doors down, G.M. wasn't above offering free or discounted extras as a means of enticing potential customers into the studio. A July 1893 advertisement, for example, warned readers of there being "only twenty-three more days in which to get an elegantly framed life-size crayon absolutely free."[1] How effective these campaigns proved to be is not recorded, but one can assume they worked well enough to help sustain G.M.'s long career.

By 1898, Deane had relocated to 224 Elm Street, and by 1900 he was at 237 Elm, now advertising his studio with the tagline of "no stairs to climb." He served as both an officer of the Texas Photographers' Association and as a member of the Merchants' Literature Club, and, in a nod to his family heritage, as a member of the Texas-Virginia Society, in which he rose to the position of secretary. The last reference to Deane as a photographer appears to be around 1938, after which time he presumably retired. Based on a letter published in the Dallas Morning News in 1938, he seems to have taken up painting.

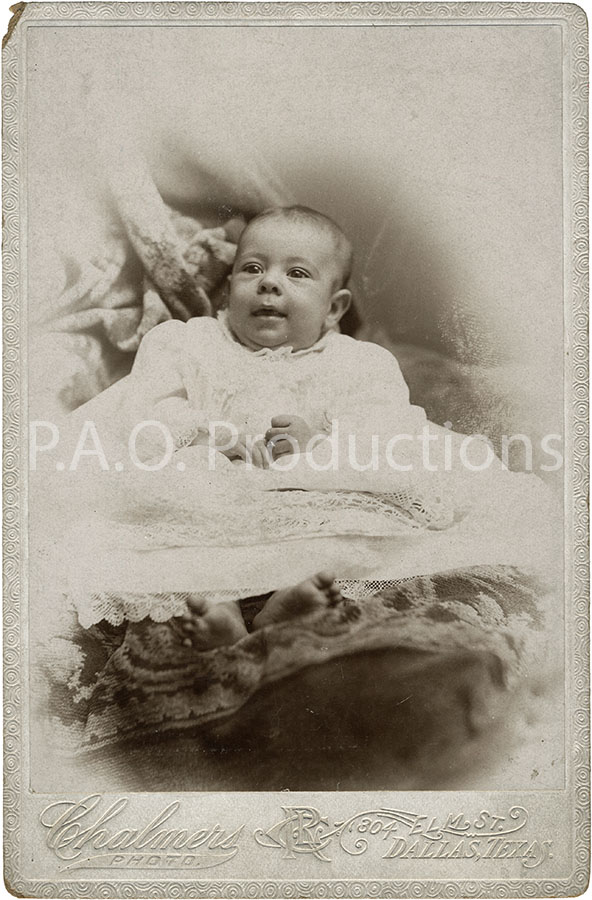

4 - R.L. Chalmers

In addition to his work as a commercial photographer, Chalmers appears to have moved about amongst the local gentry. An 1892 society page blurb notes his appearance in an Oak Cliff opera house performance of the "Convict's Soliloquy." Subsequent society pages over the next two years likewise record recitations of "Laska" and of "Othello and Iago" as part of various society programs. More ignominiously, Chalmers was party to an unspecified criminal case against him in county court which was assigned on December 6, 1893. A September 1894 notice in the Dallas Morning News likewise reports an appearance in county court on the charge of failure to pay occupation tax, a charge which was dismissed upon presentation of a tax receipt. Following that 1894 court appearance, Chalmers appears to have left the city of Dallas. Whether the legal concerns were the catalyst for this move is lost to history, but the departure marked the end of his time as cabinet card photographer in the area. User "anyjazz" of The Cabinet Card Photographers website has traced Chalmers to the city of Corsicana, where by 1900 he appears to have worked in connection with another photographer doing business on Beaton Street. Chalmers ultimately ended up in Henderson, Texas, where the U.S. Census Bureau recorded him working as a farmer as of 1920, his photography days apparently long behind him.

5 - Wisdom

It is here that what can be unearthed in the historical record becomes a bit confused. According to his January 1951 obituary, Wisdom continued to operate his studio until it was overtaken by a devastating fire "a few years later," after which time he went to work as a photo finisher and manager at the Sanger Brothers department store. Exactly when this fire occurred is unclear; the only contemporary reference I could find for a fire at 318 Elm Street was by way of a newspaper article from November 1909. According to that account, the conflagration began at the adjoining 320 Elm Street building before extending next door, leading ultimately to some $30,000 in damages. Whether Wisdom's pivotal fire was this one, or had occurred at some earlier date, is unclear, but the obituary suggests that it marked the end of Wisdom's period of independence. References to him as photographer at 300 Elm Street, not far from his former studio, are found via the 1901 and 1902 Dallas city directories, and these seem to support the timeline presented in the obituary. A further directory listing in 1904 placing him in the employ of photographer L.W. Gentry also supports this, as do the subsequent (1906 and onward) entries identifying him as an employee of Sanger Brothers. The skeleton outline which can be compiled of his later years is in a sense emblematic of the entire historical record concerning his photography career: there seems to be almost nothing available via any sources aside from the 1951 obituary and the scattered references found in various city directories. To this day, Wisdom remains something of an enigma.

6 - Williams

In a break from some of his competitors, Williams chose not to rely on ticket agents proffering deals for cheap photographs to bait potential customers into his studio. His published advertisements appear to have been considerably less frequent, not to mention less blatantly aggrandizing, than those of his contemporaries Deane and especially Apex. That being said, he was known to occasionally proclaim his as "the best cabinet photos made in Dallas," and to refer to the aristo photos produced at his studio as "thing[s] of beauty."[3] The studio's location above the Singer Manufacturing Company (they of the sewing machine fame), also likely helped grow his portrait business with both Singer employees and customers. Williams worked in Dallas until 1898, at which time he relocated to Lampasas. The historical record goes dark from there until his reported death on January 25, 1905 at the age of 73.

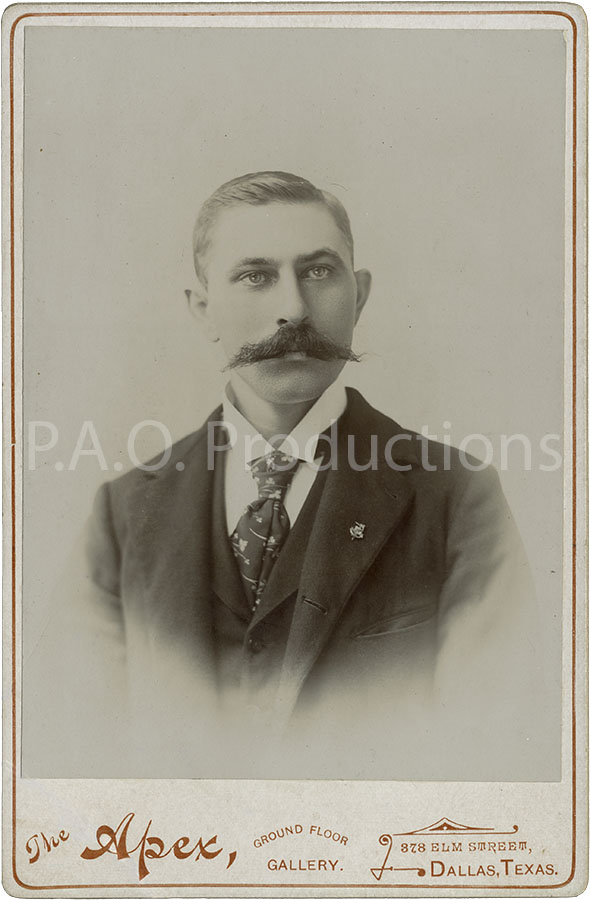

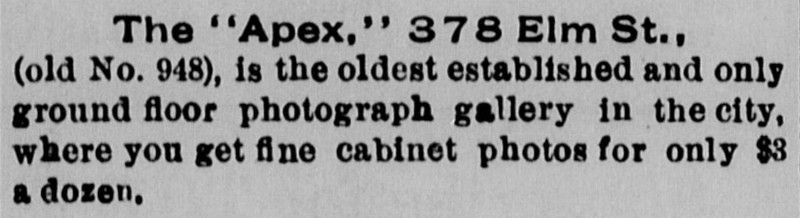

7 - Apex

"Apex" was the trade name of a photographic studio operated by William H. Parish and Joseph T. O'Bannon, two photographers who appear to have gone into business together in or about 1888. Like their competitors, their stock in trade was cabinet cards sold by the dozen. Unlike their competitors, the bravado and the sheer volume and braggadocio of their newspaper postings were unrivaled, their practice being to flood the classifieds with a veritable tsunami of short advertisements and blurbs declaring theirs as the best work on the market. In these ad placements Parish and O'Bannon routinely attempted to undercut their competitors in price, touting cabinet card prices of $3 per dozen with "satisfaction guaranteed." They additionally offered enticements ranging from "a Christmas present for every dozen photos made" to free crayon portraits with the purchase of a dozen photos. Evidently very proud of their ground level gallery in a town where the majority of competing studios were upstairs, they boldly emblazoned their cabinet cards with the words "ground floor gallery" right next to their company logo. And at one point, they succeeded in securing the services of celebrated retoucher C.F. Cook, the former employee of J.H. Webster, a fact of which they proudly boasted for several months before losing him to Webster's successor Clifton Church.

In reality, despite the Apex studio's seemingly aggressive or even cutthroat marketing tactics which saw them placing as many as seven announcements onto a single newspaper page, it's likely that the proprietors got on at least tolerably well with their peers in the local photographic community. The Parish-O'Bannon partnership, however, would prove to be somewhat short-lived. The 1888 Dallas city directory lists the two as photographers doing business at 930 Elm Street, with the first Dallas Morning News advertisements for the "Apex" studio appearing in January 1889 for 948 Elm (site of the oft-trumpeted "ground floor gallery") up the street. In 1891, this address became 378 Elm. By 1893, the partnership appears to have unraveled, with the final studio advertisements appearing in the Dallas Morning News in March of that year and the 1893 city directory being the last to mention Apex by name in connection with the two owners. Three years afterward, Parish and O'Bannon were embroiled in litigation against each other in the 44th Judicial District Court. The doings of W.H. Parish subsequent to this are lost to history, but J.T. O'Bannon continued as photographer for many more years. O'Bannon assisted in the local demonstration of an early X-ray machine in July 1897, and was a member of the Photographers' Association of Texas, eventually rising to the position of secretary. He went on to operate his own studio at 252 Elm Street before partnering with a Terrell-based photographer sometime around 1903. Newspaper advertisements for the thusly formed Schreiber & O'Bannon adopted the bravado of their antecedent, Apex, until O'Bannon's death in May 1909.

As an aside, Joseph O'Bannon was a seasoned bowler, and in 1902 was a participant in the Dallas Social Gymnastic Bowling Club. His team was the appropriately named Aristos.

It is here, at the corner of Elm and Ervay Streets, that our tour concludes. The Wilson building, one-time home of both Titche-Goettinger and W.A. Green and currently functioning (mostly) as an apartment building, now stands over the site once laid claim to by the Apex. Looking back the way we came, we get a view of a much more developed and industrialized corridor compared to what existed during the time of the nineteenth-century studios that once lined Elm Street. Here in the twenty-first century, none of their original buildings remain, but some of the cabinet cards produced within their walls survive to pay tribute to what once was.

If you are interested in learning more about cabinet card photography (and that of their smaller alternative, the CDV, or "carte de visite"), I recommend starting with the following resources:

- "Unveiling the Beauty: Exploring 19th Century Cabinet Cards through Time" via 19thcentury.us

-

Photofocus website's "History of Photography" series

-

"Identifying and Dating Old Cabinet Card Photographs" by Kimberly Powell

-

Acting Out: Cabinet Cards and the Making of Modern Photography by John Rohrbach, editor

- 1. A crayon portrait is a stylized interpretation of someone's likeness, made by printing a photograph onto drawing paper and then tracing or drawing over it.

- 2. The 1889 Dallas city directory lists W. Wirt Williams as photographer with studios over 701 and 1132 Elm. This is the only reference to 701 Elm that I came across in connection with Williams. One instance referred to 703 Elm as "Hillyer's old stand." Presumably Williams' intent was to capitalize upon Hillyer's name recognition, given that Hillyer's studio address of 701 Elm Street is well documented.

- 3. "Aristo" referred to a kind of high quality finish.

I was wondering if you have heard of DeVoe studio of Dallas? Most likely 1800s. Thank you

Wesley DeVoe’s time in Dallas dates to the early 1900s, which is just slightly after the time period I was looking at for this post (1880s and 1890s). But I can give you some information about him:

Wesley M. DeVoe was born in Ohio in 1846, apparently working in Kansas City as a portrait artist before coming to Dallas. A 1902 Dallas Morning News article describes him as “equally facile in oils, pastel and carbon, and executes many commissions of miniatures on ivory and porcelain.” The article states that he studied at the Saint Louis School of Design and that his portraiture “adorns the homes of prominent people in St. Louis and Kansas City.” Records indicate that DeVoe moved to Dallas around 1897, setting up shop at 321 Elm Street (present-day 1409 Elm Street) by 1900 and at some point apparently entering the field of photography. The 321 Elm Street location seems to have been prime real estate for photographers, having been used by Harper & Co. around 1898, by Gus B. Jackson before Harper, and by the Weatherington Bros. studio prior to Jackson. A June 1901 fire to the building resulted in substantial damage, and in July of the following year DeVoe ran a newspaper advertisement announcing the rental availability of the old location. By 1903, DeVoe had entered a partnership with photographer F.W. Voorhees at 224 Elm Street (present-day 912 Elm Street). The partnership would last until January of 1905, by which time Voorhees had decided to retire. DeVoe continued on for a few more years until his own death in (presumably) February 1908. He was interred in Greenwood Cemetery on March 1, 1908. His resting place today is in Oakland Cemetery 3 1/2 miles away.

What is not immediately clear from my research is how much of DeVos’s practice consisted of photography versus portraiture. The 1901 Dallas City Directory lists him as both photographer and portrait artist, as does it successor volume in 1902, but numerous Dallas Morning News articles appearing between 1902 and 1906 reference his skill and success as a portrait painter. Advertisements run in the paper in 1901 and 1902 advertise “portraiture,” while ads run in 1903 in partnership with F.W. Voorhees generally reference “photography” and related terms more directly. A September 1903 news article mentions DeVoe’s appearance (along with Voorhees) at the sixth annual convention of the Photographers’ Association of Texas, while a later one from June 1906 reports his commission (as painter) by members of St. Mary’s College for a life size portrait, a “piece of art.” As it was very common – routine, in fact – for photography studios to hire artists to retouch negatives and remove unwanted facial “blemishes” from subjects, one has to wonder whether this was in fact DeVoe’s specialty or perhaps even his primary function, at least during his years spent in partnership with Voorhees. I haven’t come across anything that confirms this, but it would make sense. As if to reinforce this idea, a February 1910 classified ad in the Dallas Morning News announces an exhibition for the sale of DeVoe’s paintings by the recently widowed Mrs. DeVoe.

I hope this information helps. I’ve listed my sources below:

1897, 1900, 1901 Dallas City Directories via AncestryHeritageQuest.com

Various Dallas Morning News classified ads between 1/26/1902 and 2/7/1902, and between 11/25/1903 and 12/23/1903

“Advertisement.” Dallas Morning News, Final Edition ed., 13 Nov. 1895, p. 8. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. Accessed 2 May 2025.

“Advertisement.” Dallas Morning News, Final Edition ed., 23 June 1898, p. 8. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. Accessed 2 May 2025.

“Advertisement.” Dallas Morning News, Final Edition ed., 1 July 1902, p. 6. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. Accessed 2 May 2025.

“Advertisement.” Dallas Morning News, Final Edition ed., 7 Jan. 1905, p. 9. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. Accessed 2 May 2025.

“Advertisement.” Dallas Morning News, Final Edition ed., 17 Feb. 1910, p. 10. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. Accessed 2 May 2025.

“Artists of Dallas.” Dallas Morning News, Final Edition ed., 23 Apr. 1902, p. 58. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. Accessed 2 May 2025.

“Convention is Opened.” Dallas Morning News, Final Edition ed., 30 Sept. 1903, p. 7. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current.. Accessed 2 May 2025.

“Funeral of Wesley M. DeVoe.” Dallas Morning News, Final Edition ed., 2 Mar. 1908, p. 4. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. Accessed 2 May 2025.

“Heavy Loss by Fire.” Dallas Morning News, Final Edition ed., 9 June 1901, p. 5. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. Accessed 2 May 2025.

“Industrial Dallas.” Dallas Morning News, Final Edition ed., 5 Mar. 1893, p. 4. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. Accessed 2 May 2025.

“St. Mary’s College Alumni.” Dallas Morning News, Final Edition ed., 3 June 1906, p. 25. NewsBank: Access World News – Historical and Current. Accessed 2 May 2025.